HodlX Guest Post

Submit Your Post

Money and banking: A story of values

There will be near-universal adoption of the crypto system in the next decade, and other predictions.

“I know of only three people who really understand money.”

– JM Keynes1

What will you get out of this paper?

This paper is designed to help you understand money. You need to understand what money is before you can understand the banking system. You need to understand the banking system before you can compare it to an alternative, the crypto system. Money is fundamental to life; you need to compare the two systems based on your values.

Who should read this paper?

People who want their money to work harder for them, rather than for big banks. People who want to know the reason why there are booms and busts in the economic cycle. People who want to make the world a better place.

TL;DR

Understanding money and banking will help you solve the greatest mystery in modern economics: why does our economy suffer catastrophic breakdowns, causing significant human misery, every few decades? This paper has some clues.

The development of money was a natural part of human evolution: it was driven by our biology and our values. Money arose as an extension of our memory and represented something valuable created through specialised effort, which was used by the group and then, later, exchanged with others through trade. We acquired the concept of stored memory to shift value across time periods. As we specialised further and repeated exchanges across time, this gradually led to the concept of a standard of value, the first step towards money.

Money allowed us to specialise and exchange items of value. Money is often defined using complex language, but it only has two simple, common-sense characteristics:

(1) Money needs to be scarce.

(2) Money needs to be accepted by others as having purchasing power.

Money co-evolved with our ancestors’ discovery of sacrifice. Seeds planted today, rather than eaten with a crop, could mean more next season. Borrowers could repay lenders from what was brought forth by their efforts: when the grain harvest was brought in, a certain percentage was given to those who had sacrificed. Loans and interest due were recorded on tablets and quoted in money. Sacrifice, a form of savings, and the productive use of this savings, benefitted both parties and led to a better existence for humanity.

—

1 John Maynard Keynes, British economist, cited by several contemporary sources. Unfortunately, for him, Keynes does not appear to be one of these three.

Money itself is only a symbol, a representation of purchasing power; it is not valuable in itself. Gold, US dollars, bitcoin, etc. have value only to the extent that they are scare and are commonly accepted to purchase goods and services. Since money has no intrinsic value, it must be trusted. The basis of all good money is trust, just as it is the basis for all good human relationships.

Where precious metals were present geologically most societies adopted them as money; they did this because precious metals are scarce. This allowed something that has no intrinsic value to act as a symbol that retains purchasing power over time. The global acceptance of precious metals meant that they could be exchanged for goods and services in ever distant trade and that their value was not tied to the actions of a specific nation state.

As carrying gold and silver around was somewhat inconvenient and risky, the precious metal depositories that emerged issued paper IOUs to customers, like merchants. These paper IOUs, backed by the value of precious metal, could be used for making purchases and the IOUs themselves began to circulate as a form of money. The depositories learned that not all customers demanded access to their deposit at the same time. This presented an opportunity to make loans using paper receipts for more than the total amount of precious metal that they physically held. In this way a “fraction” of the value was kept in reserve and the rest could be lent out. Precious metal depositories led to the creation of banks. Modern banks use exactly the same model today as the depositories from history.

Money: a tale of two time periods

Money and banking are inextricably linked. The history of money can be broadly divided into two periods, as set out below.

|

Time period |

Money |

Banking |

| From the time early humans began to specialise, sacrifice, and to exchange value, until the rise of precious metal depositories. | All money represented value already created, by productive effort in the real economy. This is present value (PV) money. | The banking function matched surplus capital (e.g. grain, gold) to productive opportunities in the economy. |

| From the establishment of these depositories (eventually called banks) until the present day. | Two forms of money begin to exist, side by side:

(1) PV money. For example, gold coins. (2) Future value (FV) money, where the value was linked to an expected future cashflow stream, which didn’t exist currently (at the time that the FV money was created). An example is paper IOUs or promise to pay bearer notes. |

Banking matched PV money (e.g. gold) to productive opportunities.

It also began to evolve into issuing paper IOUs in return for future cashflows from productive opportunities, in the form of loans. As both gold and IOUs were relatively scarce and were accepted as having purchasing power, two types of money existed side by side: PV money (value already created; no credit risk in exchange) and FV money (value expected to be created in the future; those who accept it take credit risk on the issuer). |

Although this evolved over time, it led to a decisive change in what money meant to humanity:

The rise of modern banking broke the historic link where money represented the memory of something valuable created.

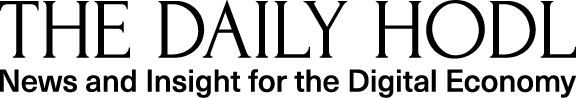

Modern, fractional-reserve banking is characterised as set out below.

- Banks create the vast majority (about 90%) of the “money” that exists in an economy. Through bank charters, society grants the exclusive right to banks to create most of the money supply.

- Banks create money by granting loans to borrowers; these loans are funded mainly by creating matching deposit accounts based on confidence in the bank. This provides purchasing power today in return for future (and greater) cashflows owed to the bank.

- Bank-created money (FV money) is explicitly linked to an asset (the bank loan), which depends on an expected future value.

- This FV money can be used for purchases today in three broad ways:

(1) for productive investment in the economy (e.g. buying equipment or hiring people)

(2) to bring forward expected cashflows (e.g. credit card finance or mortgages)2

(3) to finance asset purchases (stocks, real estate) - The repayment for (1) and (2) are dependent on future cashflow generation. Number (3), for asset purchases, is based on the expectation of selling the asset to someone else in the future at a higher price.

- This third use of funds, for asset purchases, is the main cause of excess variance in the business cycle.

- Banks accept other banks’ newly created money. These create inter-links between banks, globally. Payments between customers cause the recipient bank to retain a fraction of the transferred (deposited) money and lend out the rest, contributing further to money creation.

- If a bank’s loan value is destroyed (e.g. when asset values decline significantly), then the related FV money – originally created by the loan – is also destroyed.

- FV money destruction from the original loan leads to backward, recursive money destruction between linked banks, similar to the money multiplier process for creation on the upswing. This greatly exacerbates economic downturns.

The fractional-reserve banking system

Here is the best way to understand our current fractional-reserve banking system.

Fractional reserve banking is an inherently risky activity. The core philosophy of fractional reserve banking is based on dishonesty. The bank tells depositors that it is their money, sitting in their account, and they can have it back at any time. At the same time, the bank lends most of the money to borrowers or uses it themselves, including as an input to their own credit money creation.

If future cashflows needed to support bank loans (and the FV money that they create) do not materialise, recursive credit money destruction causes economic crises and means that the bank may not have enough reserves to cover the lie that they told depositors: that they could have their money back anytime. This is what happened in the 2008 financial crisis, prompting the bail-out of the fractional reserve banking system.

The risk structure of fractional reserve banking:

An inverted house of cards

—

2The repayment for which is based on future salary expectations.

Here are the top 3 things that banks don’t want you to know.

- Legally, you don’t deposit your money with a bank. It becomes their money; it is no longer yours when you make a “deposit”. They account for this money as an asset (since it is legally their property now). In return, you get an IOU, which they call a deposit account. An honest name for the account would be “Unsecured Loan to Us Account” but Deposit Account sounds a bit better.

- There is no such thing as deposit insurance. Unlike real insurance, the government doesn’t have a pot of money sitting somewhere to cover your deposit unsecured loan to the bank. What the government will do is print additional money to cover your loan to the bank, if the bank goes bankrupt. This would cause inflation, of course.

- Inflation is simply a way of measuring a reduction in your purchasing power. It is better called a Theft Index and is essentially a transfer of value from bank account holders to debtors. Usually, this happens just a little bit at a time, so you don’t notice the missing money. Debtors benefit from inflation because it means that they have to repay less value, in real terms. Who are, by far, the largest debtors in an economy? The government and the banking sector (remember those IOUs?). And, who is mainly in charge of determining the amount of inflation in an economy? The government and the banking sector.

Don’t feel silly if you don’t know this; banks are intentionally opaque. There is a reason you are made to feel stupid or uncomfortable when your mind wanders to thinking about how banks work, or to define what money really is. In fact, in economics textbooks and at business school, they don’t teach you that banks create money; they keep up the deception that banks are just helpful financial intermediaries, the Walt Disney version of how banks operate.

“It is well enough that people of the nation do not understand our banking and money system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning.” – Henry Ford

Robert Sharratt

Robert is part-Canadian, part-British, somewhat autistic and lives in Geneva. He is going to link the crypto system to the real economy and create a better banking model, or die trying. His interests include mountain-climbing, chess, piano, programming and distrusting authority. In his early career, he was an M&A investment banker in London, then in private equity, and then moved to Switzerland to invest his own money. He holds an MSc degree in Finance from London Business School.

Robert is part-Canadian, part-British, somewhat autistic and lives in Geneva. He is going to link the crypto system to the real economy and create a better banking model, or die trying. His interests include mountain-climbing, chess, piano, programming and distrusting authority. In his early career, he was an M&A investment banker in London, then in private equity, and then moved to Switzerland to invest his own money. He holds an MSc degree in Finance from London Business School.

ceooffice@reassurefinancial.com

Follow Us on Twitter Facebook Telegram